Last week, I had the opportunity to sit down with one of my favorite colleagues – LaRae Bennett – to talk about our shared passion: data. With decades of experience helping organizations harness the power in their data, LaRae is the living definition of a trusted advisor. She and I have the great fortune of working in data governance and analytics at a moment when the business world is finally coming to terms with how transformative capabilities like artificial intelligence (AI) can be. It’s very exciting!

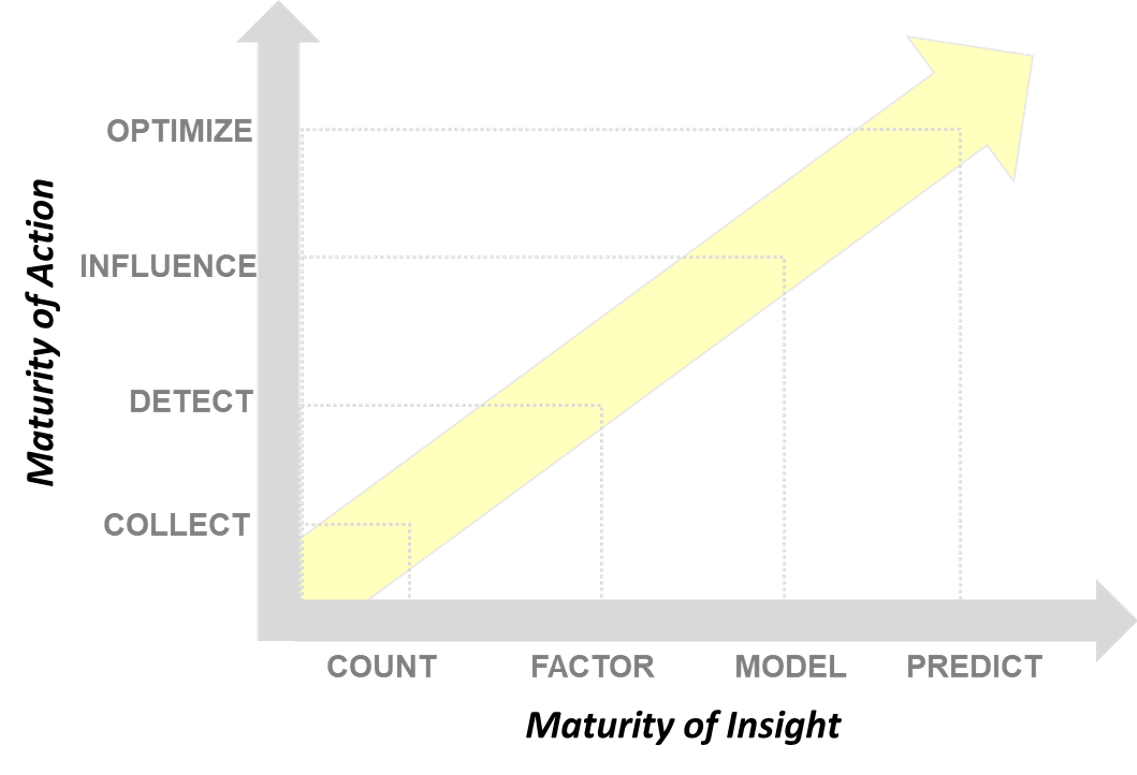

For so many organizations, the opportunity to pursue AI and other data-driven innovations is inhibited by a lack of an IT strategy and associated data strategy. As I’ve written about previously, organizations develop data and analytical capabilities through a maturity model (Figure 1). There are multiple ways to think about maturing these capabilities, but a fundamental competency of any maturity model is data governance – basically, the ability of the organization to improve the usability and trust in their data.

Figure 1. Data and analytics maturity model.

Source: Burke, J.

“It’s the big elephant in the room,” LaRae said. “There is a tendency to simply say ‘data is everyone’s job.’ While nice in principle, it doesn’t work when data is also no one’s job. That gap creates a diffusion of responsibility that can stop an organization from making any real progress.”

Business-IT Partnership in Data

Many data strategy and governance investment decisions are heavily influenced by how effectively an organization’s business and IT teams collaborate around investment priorities. LaRae shared that some of her clients were challenged in building the business case for data governance, especially when the IT organization is generating the ask.

“The data issue is really not just an IT issue,” she said. “Though the topic sounds technical, IT may not actually be the right sponsor of data governance investments. I think this is an area where a strong partnership between IT and the business really helps.”

Business leaders often experience the symptoms of poor data utility – inaccessible, incorrect, inconsistent, out-of-date, or otherwise unusable data. But business leaders may not have the experience or perspective to diagnose their challenges as being related to data governance. In addition, as IT leaders are usually focused on responsive service delivery and cost management, data governance may not surface as an obvious priority in their planning processes.

But even when it does, organizational leaders may be hesitant to pursue it.

Seven Incorrect Reasons to Avoid Data Governance

As we talked about our shared experiences, LaRae quickly enumerated seven common reasons executives cite for why their organizations have not moved forward with data governance and strategy initiatives.

- Missing technology. Many business leaders incorrectly assume that poor data utility – accuracy, consistency, timeliness, quality, etc. – reflects a gap in the organization’s technology infrastructure. Though technology can help accelerate data quality and governance tasks, many organizations can make considerable progress in data governance with little-to-no new investments in technology.

- Too time-consuming. Some business leaders report skepticism that their operational staff have the available bandwidth to contribute to data curation and governance improvements. Ironically, in most cases, these same staff would have more capacity if they were empowered to fix the data issues that compromise their productivity every day.

- Too difficult and/or expensive to fix. Business leaders that have a long history with poor data utility may incorrectly assume that any solutions to the problem will be complex and expensive. In reality, many corporate experiences with data governance demonstrate the exact opposite: simple, targeted, easy-to-implement changes can have a dramatic impact on an organization’s ability to harness data and derive actionable insights.

- Cheaper to fix on demand. Because many leaders are concerned about the difficulty and cost associated with fixing data issues, they may incorrectly conclude that it is easier and cheaper to fix data as it is needed. Unfortunately, because the organization is continuously accumulating more and more data, they are incurring an increasingly large technical debt. And because the data issues are not being resolved through a scalable approach, the debt is re-paid by every project that uses the data. In almost all cases, it is much more cost-effective to remediate a problem as early as possible.

- Missing resources and/or expertise. Some executives believe that they cannot advance data governance initiatives because they or their team members lack the requisite experience and expertise. While it is true that data governance skills are not as pervasive as some other business and technical domains, data governance is a rapidly growing sector that has gained considerable traction over the past five years. Numerous resources – free training, implementation frameworks, open-source offerings, industry conferences, consulting resources, and more – are readily available to help any organization grow.

- Waiting for some event. Perhaps due to the other barriers in this list, some leaders position data governance as an organizational capability that can wait. Typical “wait until” milestones include completing a system implementation, executing a M&A opportunity, or starting to develop AI capabilities. Yet experienced leaders know that every one of those investments moves faster, creates more scalable capabilities, and progresses with fewer risks when data governance capabilities are leveraged.

- Avoiding political risk. Some leaders perceive political risk in pursuing data governance initiatives. These initiatives require a commitment to collaborate across organizational boundaries, and they can expose operational deficits associated with bad data. In practice, data governance programs can effectively de-politicize organizational issues around data, as a) people likely already know the deficits; b) the programs provide a way of fixing the problems; and c) the programs provide a safe environment for all parties to work together and even innovate.

Taking the First Steps

So how does an organization move past these perceived barriers? As mentioned at the beginning of this article, an IT strategy and associated data strategy – especially one that establishes how an organization will integrate and manage its information assets – are extremely helpful in planning for this growth. Part of that data strategy focuses on defining an approach for data governance.

For many years, data governance programs were framed purely as top-down, enterprise-wide initiatives. Today, many experts like LaRae recommend smaller-scale projects as the preferred path to get started.

“I like to encourage clients to pick a single business process or business area they want to focus on,” she told me. “Maybe it’s new customer onboarding. We can map that business process and its associated data to understand what are the most important data quality issues. When that data is high quality, lots of internal stakeholders benefit.”

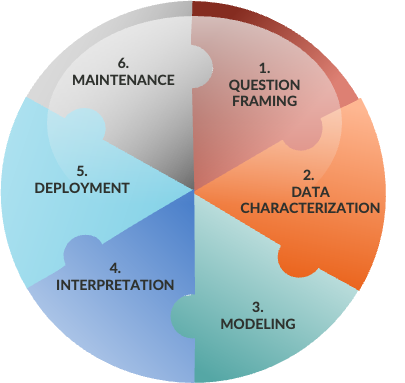

This same learning can also be applied to investments in artificial intelligence and other forms of analytics. We typically think of analytical projects as moving through a defined lifecycle that starts with clarifying the questions that need answering and ending with deploying and maintaining those insights (see Figure 2). This process is iterative, and benefits from development approaches that are agile – providing incremental advancements over time as opposed to “big bang” investments.

Figure 2. Analytical lifecycle.

Source: Burke, J.

So, as opposed to pursuing a large language model designed to incorporate millions of pages of unstructured text, pursuing a more “tactical AI” solution – something smaller that offers immediate benefit to operational staff – gives an organization the opportunity to learn how to develop AI capabilities, as well as how to address the data curation needs that such analytical models require.

So LaRae’s approach to data governance makes a lot of sense: it fuels short-term operational improvements that foster data governance champions across the organization, it fits with proven approaches for developing analytical solutions, and it enables executives to gain confidence that their investments in data governance are both safe and valuable.

So what are the barriers that are stopping your organization from cultivating better data and insights?

Jason Burke | July 10, 2023

Jason Burke | July 10, 2023